Early Music Thriving at CCM

What a difference 300 years makes. On evenings back-to-back,

the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music presented music from

the 17th and 20th centuries. It was as if one had set foot on two different

planets.

Wednesday evening (Nov. 28) in Corbett Auditorium, it was the CCM

choral series, with music by Claudio Monteverdi, a follow-up to their highly

successful performance of the composer’s Vespers of 1650 in 2010 (see review at http://www.musicincincinnati.com/site/reviews_2010/Splendid_400th_for_Monteverdi_s_Landmark_Vespers_of_1610.html).

On Thursday, also in Corbett Auditorium, the Percussion Group Cincinnati, ensemble-in-residence at CCM and the CCM Philharmonia Orchestra, led by guest conductor Neal Gittleman, celebrated the 100th anniversary of American composer John Cage with a program including Cage’s “Renga” and his “Music for Three (”the latter written for the Percussion Group in 1984. It was the conclusion of a focus on Cage this fall at CCM (see review at http://www.musicincincinnati.com/site/reviews/Celebrating_Cage_in_Cincinnati.html)

Earl Rivers, director of choral studies and head of the division of ensembles and conducting at CCM, led the Monteverdi program, which comprised selections from his “Madrigali dei Guerrieri et Amorosi” (“Madrigals of War and Love”) and “Selva Morale e Spirituale” (“Moral and Spiritual Forest”). Performing were the 37-voice CCM Chamber Choir, student soloists and a continuo ensemble drawn from Cincinnati’s early music community and beyond. Special guest was Michael Leopold, theorbo artist from Milan, Italy.

The concert was recorded by Cincinnati public television CET for future broadcast on the CET Arts Channel. Introductions to the music and the instruments were made by Rivers, assistant conductor Mare Bucoy-Calavan and the performers themselves.*

The first half was sacred music from “Selva Morale e Spirituale,” beginning with “Credidi,” a setting of verses from Psalm 116. The Chamber Choir was divided into two choirs, the better, said Rivers, to imagine a performance in St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, where Monteverdi served as maestro di cappella (the galleries of St. Mark’s helped spur the development of polychoral and antiphonal music). Sopranos Kerrie Caldwell and Danielle Adams made an affecting duo in “Salve Regina,” giving an almost literal interpretation to the words “To thee we send up our sighs, mourning and weeping in this vale of tears.” “Spuntava il dil” featured countertenor Cody Bowers, tenor Spencer Viator and baritone Jonathan Cooper, who put exquisite feeling into Monteverdi’s text about the fleeting nature of life and beauty.

“Pianto della Madonna,” the Virgin Mary’s lament at the cross, is a remnant of Monteverdi’s lost opera, “Arianna,” noted Rivers. Heartrendingly sung by soprano Erin Keesy, it was a highlight of the concert, ending with Jesus’ prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane, “let it not be as I wish, but let your will be done.”

“O Ciechi il tanto affaticar,” a madrigale morale on verses by Petrarch, dwelt on the futility of riches with calculated lightness (“where are your riches now?”). By contrast, bass Darrell Acon, gave profundity and virtuosity to “Ab aeterno ordinate sum,” a motet based on Proverbs 8:23-31 (“I was set up from everlasting”). The Chamber Choir closed the first half on an optimistic note with “Beatus vir” (“Blessed is the man that feareth the Lord”).

“Altri canti d’amor tenero arciero,” one of the “Madrigali dei guerrieri et amorosi,” is an example of “stile concitato,” the angry, agitated style developed by Monteverdi. Led by Calavan, the performance was gripping. It began mildly enough, with a lovely introduction for violins and gambas, then turned bellicose on “I sing of furious and fierce Mars’ harsh clashes,” sung by the men of the choir, with baritone Stefan Egerstrom fielding rapid repeated notes and daunting coloratura. The madrigal, dedicated to Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III, concluded with an appropriate salute, filled with polyphonic dignity and grandeur. “Vago augelletto che cant ado vai,” based on a sonnet by Petrarch about birds commiserating with mankind, was simple and charming by contrast.

The “Lament of the Nymph,” a canzonetta in three movements, with text by Ottavio Rinuccini, was thoroughly dramatic, with soprano Xi Wang and tenors Jason Weisinger, James Onstad and Nicholas Ward positioned facing each other. The men echoed her sorrow with picturesque lines of their own in the monodic, recitative-like style of the period (“stile rappresentativo”). “Dulcissimo uscignolo” (“Sweetest Nightingale”) for two sopranos, countertenor, tenor and baritone was wistful, longing and ineffably sweet.

The Chamber Choir closed the set and the concert on a fiery note with Monteverdi’s only eight –part madrigal, “Ardo, avvampo, mi struggo, ardo: accorete,” “I burn, I blaze, I am consumed.” Several men’s voices trailed off at the end with “allow your heart to burn to ashes and be silent.”

Enough cannot be said of the continuo ensemble and their performance throughout the evening: the pure-toned violins, with their softly swishing open strings, the gentle harmony of the lirone and harp, the burnished tone of the viols and violone and the multi-colors infused by the keyboard instruments and lutenists Stucky and Leopold.

Pappano and Montgomery served as lead coaches for the "Monteverdi Project." Dates for the CET broadcast will be announced at a later date.

*A

bestiary: Viols are members of a string family that preceded the modern

violin family. They come in two types, violas da braccio (arm viols, held

under the chin like violins) and violas

da gamba (held between the legs like cellos). They were played by James Lambert, Annalisa Pappano,

and Kivie Cahn-Lipman. Lambert also played violone, ancestor of today’s double bass. Cahn-Lipman also played cello.

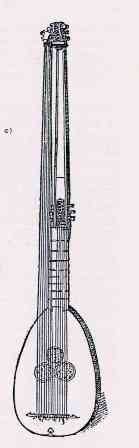

What’s a theorbo? Arresting-looking, for one thing, as attendees at the CCM concert noticed immediately. Arresting-sounding, too, accounting for that wonderful bass fundamental heard in anticipation of cadences or phrase endings during the evening. As Leopold explained, the theorbo is a six-foot-long bass lute, popular in the 17th to early 18th centuries (Leopold often plays it for performances of baroque opera.) It has two sets of strings, one tuned in fourths with a fretted fingerboard (with notes played stopped and unstopped), the other comprising an 8-note, octave-spanning scale, with the strings played unstopped.

A lirone, explained Pappano (artistic director of Cincinnati’s early music ensemble Catacoustic Consort and an adjunct faculty member at CCM), is a viola da gamba-like instrument designed for chordal playing and customarily used to accompany the voice. Rodney Stuckey played both archlute (a kind of small theorbo) and baroque guitar (a small guitar). Jennifer Roig-Francoli and Yaël Senamaud played baroque violin, visually very similar to the modern violin. Vivian Montgomery (also of the CCM adjunct faculty) played harpsichord. Montgomery and Jaying Gan played portative organ. Elizabeth Motter played baroque harp.