Tüür's "Wallenberg" Stinging, Timeless and an Operatic Cyber-First

(first published in American Record Guide, September-October, 2008)

“What I do is not enough, but it would be a start.”

Holocaust hero

Raoul Wallenberg and his nemesis Adolph Eichmann both sang those words in Estonian composer

Erkki-Sven Tüür’s “Wallenberg” at the

Good versus evil,

myth making, and modern tragedy all reside in this powerful opera (Tüür’s first), inspired by the

Swedish diplomat who saved an estimated 100,000 Jews in Budapest at the end

of World War II, only to be sent to the Gulag by the occupying

Russians.

It was commissioned and

premiered by Dortmund Opera in 2001, with a tightly crafted libretto by German

playwright Lutz Hübner. The

When Bertman's production was first

presented in 2007 in Tallinn, it marked a probable first in operatic history: after the removal of a Soviet war monument

from central Tallinn in April, the Russian government forbade Bertram to travel

to Estonia (he was allowed to attend the June 1 premiere). Undaunted, Bertman asked Estonian director Neeme Kuningas and designer Ene-Liis Semper to

follow through with his staging.

Rehearsals were held over the Internet, using online pictures from the

stage.

Bertman, enfant terrible of Moscow’s Helikon

Opera, gives "Wallenberg" a universal aspect as opposed to the Dortmund production, where Nazi

symbolism dominated. His view is

timeless, as if "from the 42nd century," Bertman said.

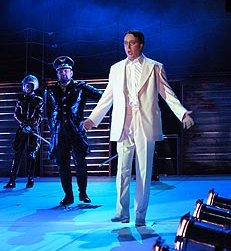

The diplomats were ornately dressed, with

powdered wigs and heavy makeup. The

Germans wore black leather and carried light sabers. The Jews had prayer shawls. The Gulag prisoners were in rags.

Russians wore red. Wallenberg was dressed in white, with a prayer shawl

after his first rescue failed. Eichmann,

sung by bass Priit Volmer in a sepulchral tessitura, swept on and off the stage in a black

leather cape, with silver epaulets and a white wig.

It is a stinging satire – two acts and 19

scenes, moving from Stockholm and Budapest to somewhere in the Gulag.

A Star of David took shape in the darkness

as members of the Estonian Opera Chorus, each holding a candle, gathered

on stage in the Prologue to muse about Wallenberg.

Several scenes centered on a long banquet table

bathed in color – gold in Stockholm, black in Budapest (for Eichmann’s

reception), red in Moscow, where a pair of comical Soviet offices clutched mikes

and mimicked the doublespeak given by the Russians to inquiries about Wallenberg over the years.

There were three Wallenbergs: the diplomat,

heartbreakingly portrayed by Estonian baritone Rauno Elp, Wallenberg-as-Elvis

Presley, who cruelly taunted his alter ego in captivity (tenor Mati Turi), and a

yogi in loincloth who performed amazing contortions in the final scene as a

Jewish mother repeated offstage a haunting description of her family in ashes.

The 19 singing roles included diplomats with

funny walks and a quasi-rapping German officer whom Wallenberg intimidated

Scarlet-Pimpernel-style (the real Wallenberg was influenced by the

1941 film "Pimpernel Smith," where a character based on the fictional French

revolutionary hero outwits the Nazis). There was a woman who tried to comfort

Wallenberg (there are no love scenes in the opera), the Jewish mother, movingly

sung by Aile Asszonyi, and a trio of Gulag prisoners grateful to have shared

confinement with the famous man.

’Wallenberg Circus,’ the grossly irreverent

finale, opened with a merry little waltz sung by the chorus. Everyone was there to join in, including

Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, a Russian matryoshka (nesting doll), Americans, Russians, and

characters from earlier in the opera – even the ever-spiteful Eichmann. A smiling Ronald Reagan sang of making

Wallenberg an honorary American citizen (which he did in 1981). A spastic American general bragged about

Wallenberg, whose mission was in fact partly sponsored by the U.S., and Jacob

Wallenberg basked in his nephew’s celebrity.

Reagan look-alike, baritone Väino Purra, had four hands. Two of them were

Eichmann's reaching from behind Reagan's back.

The Estonian National Opera Orchestra, led by Music Director Arvo Volmer, went Bayreuth one further by performing completely out of sight beneath a raked stage floor (Volmer’s idea). TV monitors supplied sight lines for the singers, and helped temper Tüür’s brass and percussion-rich score for the 700-seat, neo-classic theater.

Tüür's pungent,

post-modern score makes no concessions to neo-romanticism. Painful stabs of brass occurred often, and

his use of tubular bells for alarms recalled his mentor, Estonian composer Lepo Sumera’s Symphony

No. 2. Traditional harmony and melody

happened at telling moments, such as Wallenberg’s first entrance, where he was wreathed in a

warm halo of sound. The ‘Death March’

was appallingly catchy, with SS troopers “walking” their fingers and drumming

their hands as Jews were stripped of their coats en route to