Paavo's Pictures: Star-Crossed Debut

This is the

first of “Paavo’s Pictures,” a retrospective of Paavo Järvi's tenure as music director of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra that will run on this site during the orchestra's 2010-2011 season, his 10th and last as music director. The series begins on September 11, 2001.

Star-Crossed

Debut

September 11, 2001 -- a Tuesday -- began like any other day for Paavo Järvi.

Except that this was to be his first rehearsal as music director of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra.

A week of celebration lay ahead, culminating in his September 14 and 15 inaugural concerts. He was 38 years old, brimming with enthusiasm and full of plans for his new American orchestra.

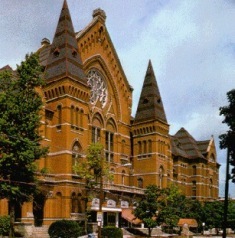

It was just after 9 a.m. when he entered Music Hall, the red brick, Victorian-Gothic landmark that dominates Cincinnati’s “Over-the-Rhine” district.*

The guard on duty nodded as he strode

into the hallway backstage, a briefcase full of scores under his arm.

An ashen-faced Steven Monder waited outside the newly decorated conductor’s suite. The CSO president cast him a look of distress.

“Have you heard what happened in New York?”

It was obvious Paavo hadn’t, having driven straight from his Spartan loft three blocks away with no thoughts other than the music he was going to make with the orchestra that morning.

Monder accompanied him to his office where coffee waited, steaming hot in a black mug inscribed “Paavo Järvi Season One.”

Paavo sat and listened, incredulous at first. But it soon became clear that this was no joke from the characteristically jocular Monder -- startlingly clear: His debut at the helm of a major American orchestra, a goal since arriving in the U.S. as a 17-year-old émigré from Estonia, had been caught in the wake of a major American disaster.

What to do? Paavo felt like his ship was steaming away from the dock.

Rehearsal was at 10 a.m. Orchestra members took their seats quietly. The air was heavy with questions. Questions with no answers. Like everyone on that fateful morning, Paavo and his 100 musicians would have to wait and see what “911” meant for them and for the rest of the world.

Rehearsing American composer Charles Coleman’s “Streetscape,” a world premiere commissioned for the inaugural program, helped ease tensions. Its infectious rhythms and sparkling newness were a distraction from the awful news of the day. Ironically, “Streetscape” is about New York, Coleman’s hometown, which gave it poignancy and immediacy in light of the agony playing out in his own neighborhood that day.

A week of welcome had been planned for Paavo’s Cincinnati arrival. There was to be a street fair echoing Coleman’s “Streetscape” on Elm Street outside Music Hall preceding each concert. A gala party Thursday night in the Music Hall ballroom and a flurry of media events. The concert was to be telecast live, the first time for a CSO concert in over two decades. Guest artist was Norwegian cellist Truls Mørk in Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1.

Now all flights in the U.S. were grounded. The country was on high alert and the borders were closed. Mørk would not be able to make the trip from Europe. Coleman would have to find another way to get to Cincinnati. People were hunkered in front of their TVs watching an apocalypse unfold. No one seemed to know where President Bush was.

The first casualty for the CSO was Mørk, who would have to be replaced. No one could reach Coleman, who lived in Tribeca, in the shadow of the World Trade Center. Monder and his staff manned the phones, trying to sort it all out.

Staff members huddled with Paavo at the rehearsal break. Should they cancel the concerts? Music Hall, with its 3,500 seats, was a near sellout, but would people come? Or would they stay home, glued to their TV sets trying to digest the national tragedy? Would a change of program be necessary?

Rehearsal continued with Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. Heroic sounds filtered backstage as conductor and musicians poured their energies into the music.

By mid-afternoon, Coleman had

called to say he was unharmed and was piling into his car for the 10-hour drive

to Cincinnati. With the bridges closing

and New York shutting down, there was no time to lose.

Paavo complimented the orchestra warmly as the afternoon rehearsal drew to a close, drawing a smile from concertmaster Timothy Lees and a stamping of feet from the musicians as they “applauded” their new conductor.

As he stepped off the podium, Monder came onstage to make the announcement to the orchestra. The concert would go on. Debussy’s “La Mer” would be substituted for the cello concerto and the program would open with Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” as a memorial to the victims of the day’s horrific events.

The street fair and welcoming party were canceled. The telecast would go ahead as planned. (The street fair never took place; the party was re-scheduled for December.) Members of the media, standing by for an update from the CSO, were contacted. Media relations manager Nellie Cummins briefed the reporter from The Cincinnati Post by phone.

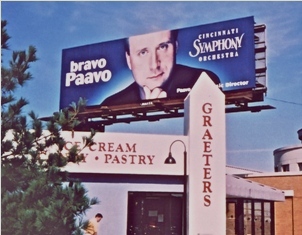

Cummins had been closely

involved in the planning and implementation of the inaugural events. “We’re going to splash the boy all over

town,” she enthused earlier in the month as “Bravo Paavo” billboards and

banners sprouted across the city. The

CSO had obtained a special marketing grant to make the most of what is a

pivotal event for any orchestra, the appointment of a new music director. Cummins’ voice was heavy with sorrow as she

said the celebration would have to be canceled.

Paavo was philosophical: “This is a surreal time in history. Everything seems trivial next to this. You just don’t see two towers disappear. It doesn’t happen anywhere other than movies.”

The country was in mourning. Flags flew at half-staff flew all over town, often sharing space on buildings with “Bravo Paavo” banners.

Music Hall was barely two-thirds full opening night. Some people merely assumed it had been canceled. Others were too distracted to attend. Travel restrictions forced most out-of-town critics to stay away.

The young conductor strode assuredly to the podium, a striking figure in formal attire, blue handkerchief peeking from the pocket of his jacket (blue, black and white are Estonia’s national colors).

“The Star Spangled Banner,” traditionally performed at each season’s opening concert, took on added fervor as audience members sang with their hands over their hearts. Looking back on it, Paavo expresses surprise at how nervous he was as he announced the dedication of Barber’s elegiac Adagio with the TV cameras rolling. If he had known a cellist would collapse during “Streetscape,” bringing the performance it to a halt, he might have had further jitters, he said. (It turned out to be a fainting spell and Paavo returned quickly to the podium to report softly, “He’s OK,” to the startled audience.)

Coleman, 32, red-haired and energetic, who had arrived safely in Cincinnati, rushed to the stage to embrace the conductor and acknowledge the crowd’s warm response. (“Long may you wave!” he had inscribed on Paavo’s score.) It was lost on no one that Coleman’s “Streetscape” had an eerie resonance in the wake of the Twin Tower disaster.

The ovation for Cincinnati’s new music director after the final, uplifting bars of the Tchaikovsky was long and heartfelt. There were shouts of “bravo” and “yes!” Everyone agreed the concert had been a resounding success.

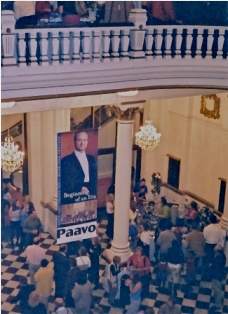

Paavo came to the Music Hall

foyer after the concert to share his feelings with the audience. The orchestra had considered canceling the

concert, he said. “Music has tremendous

healing powers. I am so happy we

didn’t.”

His words advanced that healing and helped forge a bond with his new city.

*”Over the Rhine” is named for a canal that used to flow through downtown Cincinnati, bordering what was a busy German-American neighborhood during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Central Parkway marks the site of the canal today.