Thoughtful Program for Pearl Harbor Day

This weekend’s

Cincinnati Symphony concerts might have been authorized by an act of Congress.

Friday is “National

Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day” and according to 36 U.S.C. §129, “The President is requested to issue each

year a proclamation calling on the people of the United States to observe

National Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day with appropriate ceremonies and

activities.”

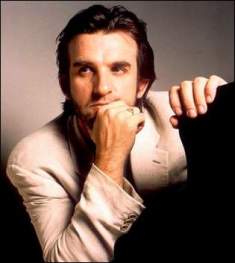

The CSO, led by Polish

guest conductor/composer Krzysztof Penderecki, will do just that at 8 p.m.

Friday and Saturday at Music Hall.

Penderecki, one of

the pre-eminent composers of the last half-century, will lead his “Threnody for

the Victims of Hiroshima” and the world premiere of his newly revised Piano Concerto,

“Resurrection.” Soloist in the concerto

will be Irish pianist Barry Douglas.

“Performing

“Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima’” on the

As the artistic

head of the CSO, Järvi is ultimately responsible for selecting the

programs. He has shown a flair for

linking repertoire with history and current events, as shown in CSO concerts he

conducted last season coinciding with Election Day and Veterans Day. The former included Shostakovich’s

“Leningrad” Symphony, a 1941 composition that landed the composer on the cover

of Time magazine and helped spur the war effort against Nazi Germany, and the

light-hearted “Slava: A Political Overture,” dedicated to the late Russian

cellist and Soviet dissident Mstislav Rostropovich. Järvi’s Veterans Day program went even

deeper, contrasting Mahler’s questing, valedictory Symphony No. 9 with Olivier

Messiaen’s unquestioning affirmation of faith, “L’Ascension.”

This week’s

Penderecki pairing is equally interesting from a purely aesthetic point of view. (The CSO has dubbed it “The Bold and the

Beautiful.”) “Threnody,” which vaulted

Penderecki to fame in 1960, represents mid-century modernism at its height. The Piano Concerto, written in response to

911, reflects the return to tonality that took place in classical music in general

during the last quarter of the 20th century.

The concert will

open with one of history’s great experimenters, Beethoven, in this case his Symphony

No. 4.

“Between my two

pieces are actually 40 years, but it sounds like 100 years maybe,” said

Penderecki, by phone from

The contrast between “Threnody,” where a

string orchestra spends nine minutes trying not to sound like one, and the Piano

Concerto, a sort of updated late romanticism, could hardly be greater.

Despite their

titles, neither work began life with any extra-musical associations.

Composed when he

was 26, “Threnody” is actually an abstract work. Its original title was 8’37” (“Eight Minutes

and Thirty-Seven Seconds”) after the famous 4’53” by American composer John

Cage. It has no program. After rehearsing it, Penderecki recognized

its emotional impact and decided it needed a contextual reference. The victims of

“Threnody” is a

“sonic” work not based on the traditional building blocks of melody, harmony

and rhythm. Scored for 52 solo strings,

it utilizes the instruments in unconventional ways. Sound masses and pointillistic layers are

organized into segments measured in seconds.

The final 30-second tone cluster has all 52 players on different pitches

fading from very loud to very soft, simultaneously moving their bows from the

bridge to over the fingerboard.

Even the notation,

Penderecki’s own using graphics instead of bar lines and measures, was novelty

for its time. There are symbols for

altering pitches, tapping the instrument, bowing behind the bridge and so on.

“I had to invent

this notation to be able to write this piece, which actually was influenced by

electronic music,” he said. “I was

working in an electronic studio and I wanted to transcribe sounds which were

impossible to produce on stringed instruments.

The result is that the string orchestra doesn’t sound like a string

orchestra. It sounds more electronic.”

Some conductors use

a stop watch to conduct “Threnody.”

Penderecki does not. “This piece

has changed in my mind many times through many performances. I like to be free conducting, not just to

count seconds. That would make it

impossible to make music. The proportions

remain the same. I always need time to

explain the notation, but it is actually easy to play. It doesn’t require technique, really. I did

it also with children’s orchestra.”

During the late 60s

and 70s, Penderecki turned away from severe modernism and began cultivating a

more tonally based, neo-romantic style.

He became known for large choral orchestral works like the “St. Luke

Passion” and “Polish Requiem,” which also reflected his support of the freedom

movement in

Then 911 happened.

“It was a shock for me. After that, I was not

in the mood to write a capriccio. I

decided the piece had to be serious. I

wrote a chorale and called it “Resurrection’ (without a text). I started to write it from the

beginning. It is a completely different

piece.

Though inspired by 911, the work is universal

in its meaning, he said, as “a symbol of life’s victory over death” and the

consolation of faith. The chorale -- not

a quotation, but written in the style of 17th-century Lutheran

chorale -- plays a larger role in the new version, which has an expanded

finale.

“I decided after

the premiere that the piece was too short.”

The Concerto grew by about eight minutes, “an essential change,” he said. “Now it will be 36 or 37 minutes. It is not a typical three movement concerto,

but a kind of symphony concertante. The

orchestra has equal parts as the piano.”

Douglas, who has

played the Piano Concerto all over the world, calls the new ending “rousing”

and “almost swing-like. A truly great

concerto just got greater.”

Penderecki, 74, has

won the Grammy for Best Classical Contemporary Composition twice (in 1988 and

1998, for his second cello and violin concertos). He is often asked about his evolution from

1950s avant garde to his current, more accessible style.

“I don’t like to

stay in the same musical idiom. I’m

always trying to find something new. To

find something new, you have to go back sometimes and be inspired by it.”

Commentators have

remarked that Penderecki’s embrace of more traditional forms coincided with the

beginning of his career as a conductor in the 1970s. Or that his borrowing from the past reflects

a conservationist instinct analogous to the arboretum he maintains at his

country home near

“I like to write

music there. It is a remote place, a big

park, about 70 acres. I am collecting

trees almost 35 years (his German great-grandfather was a forester).

Penderecki has

guest conducted in

“I like this orchestra. It’s like returning home,” he said.

Guest conductor/composer Krzysztof Penderecki leads the CSO at 8 p.m.

Friday and Saturday at Music Hall. On

the program are Penderecki’s “Threnody to the Victims of

(first published in The Cincinnati Post Dec. 6, 2007)